I drew inspiration to write this after listening to two excellent podcasts.

On an older episode of Pod Save the People, the hosts discussed a New York Times story detailing racial disparities in how child protective services were being utilized (Skip to 0:10:50). Embedded in this discussion was the fact that the number of calls to child protective service agencies seems to be increasing in recent years.

On The Weeds, the co-hosts were analyzing a whitepaper that detailed the potential impacts on shoplifting that can be realized by changing the way welfare benefits are delivered (skip to 0:58:00). Ezra Klein had to take a moment from an otherwise technical conversation to stop and reflect on a grim implication. Some of these benefits are for children. And caregivers are stealing food to feed them. It reminded me that sometimes it takes effort to make the connections between policy and impact, but those connections were always there, waiting to be found.

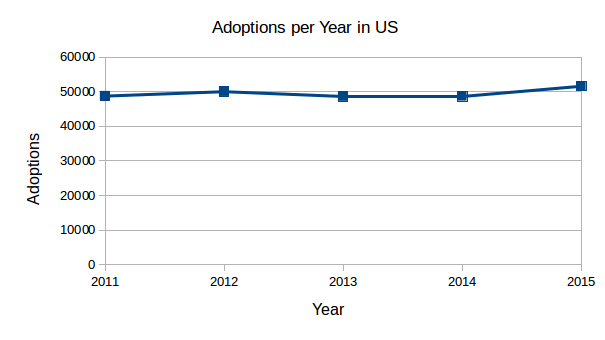

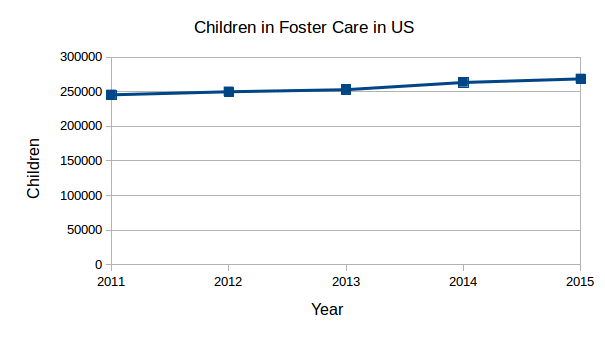

I decided to try to dig into some data to figure out if there is a current trend in child welfare in terms of foster care and adoption programs. This let me to the US Department of Health and Human Services website, which allowed me to download source data for 2011-2015 for a few meaningful statistics. I had to manually sum together state-level info from that site to create these charts, which show nation-wide stats.

I’m not going to claim to have invented the idea that issues are complicated, intertwined things. Everything is connected. But over this past year I’ve been seeing the issue of child welfare front and center in everything I observe, and it has been startling.

We’re faced with a crisis in two forms. We seek to reduce the number of children entering the foster system, and we seek to get those in the system adopted into permanent homes. This appears to be a problem of related rates, of input versus output. Certain forces impact the flow of children into the foster system, and other forces impact the rate at which they are pulled into permanency. These dual challenges have very different root causes and possible solutions. The numbers show that we’ve got space to do more on both.

The Supply Side

Every tragedy, big or small, has a chance to produce a new foster child.

For example, take the fact that we’re suffering through a nationwide opioid epidemic. Think about the staggering numbers of deaths and addiction rates we’re seeing, and ask yourself, what percentage of those are parents? How many of those households have kids in them, and how many of them are about to attract the attention of child protective services? I suspect, with a lag, we’re going to see the number of new foster children spike, with the worst impacts being geographically concentrated to areas hit particularly hard by this crisis. Unfortunately, the HHS data stops at 2015, so I cannot back this up yet. Let’s just add that to the list titled “Unpleasant Opioid Stats We’re Not Looking Forward to Seeing Next Year.”

These kids are the tragic amplifiers, impacted by every social and political injustice conceivable. Every new addiction, every overdose, every eviction, every bankruptcy, every untreated mental illness, every lost job, every prison sentence, every deportation, every catastrophic weather event, every violent crime. All of them have a feasible path that ends with a child in the system.

And then they do find permanency? They find themselves carrying traumatic loss but living in a world that stigmatizes mental health issues. This is a difficult burden to take on. An unfortunately non-zero number of parents will choose to “disrupt” an adoption after a placement, for whatever reason, putting the child back into the foster system.

There’s a darker side here too, where the threat of separation is weaponized against people of color and those living in poverty. “Sure, you can call the health department, but I could call child services about the conditions your child is living in. Your move.” As an adoptive parent I have a lot of complicated feelings here. How many of these children did not actually even need to be removed in the first place?

The Demand Side

I’m going to speak from personal experience when I say that adopting a child is not easy. Nor should it be. But that difficulty thins the pool of prospective adoptive parents. Massachusetts makes a series of concerted choices to take finances out of the equation. Our state provides intensive training and post-adoption support services to guide parents through the process. Adoptive parents can qualify to keep their stipend and continue Medicaid coverage. And foster children in Massachusetts get free in-state tuition, whether they were adopted or not.

These are incentives to encourage and enable adoption, by taking finances out of the parents’ decision-making. And they are expensive. States that are not so generous with taxpayer dollars, states like to tout their low tax burden, are not going to have such incentives to offer.

Stepping back, in terms of state and federal policy priorities, the most obvious knob is straight up funding for child welfare services. This puts our legislatures in a position to set the priorities of these services in terms of funding. Underfunded and understaffed departments won’t be able to keep up.

Moreover, these kids are going to need services. They tend to enter the system with physical, psychological and developmental complications far beyond their typical peers. But education is also a major funding sink for local and state governments. Public school budgets bear the burden of special education needs, as they carry a mandate to provide services to children who need them. Private schools are under no obligation to provide such services. What happens to that budget when we start picking away public school funding for voucher programs? Public schools will struggle to provide services, and adoptive parents will struggle to make due without.

And what about health care services? These kids can’t get on their parents’ plan because while they are in foster care their legal guardian is the state. So the state foots their bills; in MA, for example, they get Medicaid. But Medicaid funding is clearly not immune to politics. If it suffers, so do they. Cuts to budgets will impact reimbursement rates, and those rates drive the number of providers offering their services. If you don’t believe we, as a nation, would ever endanger funding for children’s health care, I’d refer you to the fact that we’re already doing so.

Too often, when we talk about the welfare state, our conversation focuses on personal responsibility. On individuals who find themselves dependent on the government because of personal choice. Dead beats. Welfare queens. Well, the real welfare queens are actually princesses, and they didn’t seek this lot. These children provide the most lucid justification for the social safety net. The free market? The invisible hand? It doesn’t give a shit about them, whether they can eat, see a doctor, go to college, or find a safe forever home. It’s up to us, the public, to decide how to react to this situation.

Our policy decisions in this area revolve around creating an incentive for prospective parents to adopt a child by ensuring a certain level of support. The robustness of these support structures will determine the strength of the incentives generated. Every policy choice even tangentially related to child care will have an impact on the number of families willing to make this commitment.

What Do We Want?

Let’s take a moment to step away from details and get purely idealistic. Look back on those two graphs. The number of children entering foster care should be vanishingly low. And the number of adoptions should hold at a level to cover the removals that were truly unpreventable. That’s a close to a perfect world as we can get.

I’ll acknowledge that our world is far from perfect. But these ideals should form the foundational principles of what we wish to achieve. A moral compass that we shouldn’t lose sight of. Because if we look hard enough, we can find connections to these goals wherever we look.

Everything you think that matters flows down into this. Whether it is a crisis driving the swelling ranks of children removed from their homes, a support structure that could have been in place to mitigate it, or a challenge these children face on their path forward, every issue trickles down to them. These young people, who have had so little agency over their own fates, are depending on us. Let’s choose carefully.