Video games have been portraying warfare since its first days as a medium. Media critics pointed out that the Medal of Honor series set in WWII went on longer than the actual conflict it used as a setting. And like all war media, video games cannot escape the question of portrayal versus endorsement. Do these games celebrate and glorify war, or criticize it? As with all media, it depends on the product.

The top First Person Shooter games from the last decade been battle royale games that focus on last-man-standing fights set outside any specific conflict or narrative, and range from dystopian and nihilistic (Playerunknown’s Battlegrounds) to irreverent and goofy (Fortnite). But none seemed to be interested in interrogating their settings.

Then came Escape from Tarkov, by Russian development studio Battlestate Games. The gameplay loop was unique at the time (it has since established the “extraction shooter” genre, which has several competitors at this point). In Escape from Tarkov, players equip themselves from a persistent inventory, and are dropped into a large map simultaneously. The goal is to reach fixed extraction points some distance away. Should you die, you lose everything you came in with. Should you extract successfully, you keep everything you’ve collected along the way.

While it does not attempt to make its stance obvious, I believe that Escape from Tarkov has a subtle anti-war message buried beneath its military-simulation-shooter exterior. This thesis is conveyed, primarily, in the mechanics it lays out and gameplay loop it creates. It is further reinforced by the loose narrative that surrounds the setting. Let’s explore both.

Heads you lose

In its current (Beta) state, you are never told that you won a game of Escape from Tarkov.

That may seem like a strange idea, as many players finish rounds of this game (“raids”) with a euphoric rush of victory and accomplishment. Before we interrogate the end-state of an Escape from Tarkov raid, first let’s look at some peer FPS games to see how they compare.

These are the end-game screens from Counterstrike: Global Offensive, Call of Duty: Modern Warfare Warzone, Battefield 4, and Playerunknown’s Battlegrounds. Notice the terminology being used. The feedback to the player is unambiguous; you won. It is celebratory and congratulatory, which is intuitive considering the “win” state is the goal of any game.

Now, let’s look closely at how the possible end states of an Escape from Tarkov raid are presented to the player.

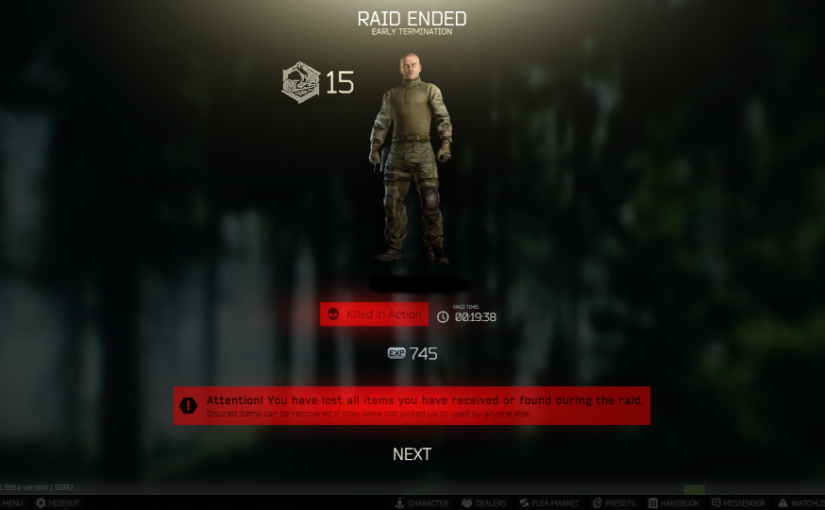

This one I see more often than not. Simple enough. You died. Everything you brought with you is left behind.

And this is the screen you get if you successfully extract. Note again the choice of wording here. You didn’t “win”. You didn’t achieve “victory.” You get no chicken dinner. You just survived. Your reward is that you get to keep trying, and maybe came out of the raid richer than you went into it.

And this internal contradiction continues to play out over time. It may be a symptom of the game’s perpetual “beta” state, but there’s no end to Escape from Tarkov. You can level up, complete all the quests, and your rewards are access to better guns and better gear. Which you then take into increasingly dangerous locations to seek out harder fights. The loop persists, but as many have noted, the only way to “escape” from Tarkov is to stop playing.

Pacifism Rewarded

The above “Survived” screen is not the most common outcome for the average player. Even competitive streamers, at the top of their games, tend to boast approximately 50% survival rates. I’m no pro gamer, but I’ve been playing this game on and off for years. At last check, I’m sitting at 46%.

The reason for these low survival rates is the sheer merciless brutality of the game’s damage model. Escape from Tarkov sports an extremely low “time to kill” for most weapons. As such, that the first player to see their opponent in any engagement is probably the winner. Fights often end in a single shot. Since players move about the maps freely in any direction after spawning, they will often be dispatched by an enemy they never saw. Therefor, death is not only deeply consequential as a setback, but often simply unavoidable. Plenty of games have unforgiving damage models, but few also take progress away from the player when the player is killed. The combination of the two is famously demoralizing.

It is also worth noting that, besides the potential loot or quests, there’s no guaranteed reward for killing another player. It is frequently a better choice to avoid combat rather than seek it out. A player can extract, with piles of loot, after completing multiple quests, without actually having fired a shot.

A game that wants to celebrate violence would go out of the way to encourage it. It would reward the player for any successful engagement. Escape from Tarkov does neither.

This is my weapon. There are many like it, but this one is not mine.

Escape from Tarkov is a love letter to modern firearms, with a commitment unmatched by any game I’ve ever played. It undertakes a level of customization that maintains fidelity both visually and mechanically to real world weapons and equipment. The variety of platforms is massive, and the options for tweaking and altering them are countless: gas tubes, receivers, magazines, rails, tactical lights, scopes, and optics can be mixed and matched to create a weapon that is unique.

It may initially appear unlikely that such a degree of commitment to faithful recreations of guns could be paired with an anti-war message. Likewise, plenty of games allow you to customize your gun to different extents. But the most important core mechanic of Escape from Tarkov is that you lose everything upon death. That rifle you painstakingly modified to suit your needs? One mistake, one false move, or even just a stroke of misfortune, and it’s gone. Your enemy carries it off to continue his killing spree, or just sell it for parts.

Attachment to your equipment, and the so-called “gear fear” it creates, is misguided. Thus, Escape from Tarkov manages to shoot a narrow gap between clearly caring deeply about firearms while refusing to let the player celebrate them as their own personal plaything. That gun was never yours. You were just holding it for the next player who kills you.

Skirting Nationalism

If you are really interested in the lore behind these games, or just want to watch a decent war movie, I highly recommend the short film series Raid. The series is set in the game’s universe, and provides some exposition into the setting. It can be found on YouTube here.

The core conflict at the heart of the narrative in Escape from Tarkov involves a proxy war being fought between major world powers by way of paramilitary contractors (PMCs) rather than direct war between nations. As such, players create characters that are aligned to one of these PMC factions, not to any real or fictional nation. You’re just a mercenary, and you’re fighting other mercenaries.

Although the Russian-aligned “BEAR” PMC faction is initially represented as sympathetic in the Raid films, the narrative and mechanics emphasize that every PMC player is on their own, having been left behind by their employers.

Escape from Tarkov’s imagery borrows heavily from Joseph Conrad’s novella Heart of Darkness, even going as far to name one of its pre-order packages the “Edge of Darkness” Edition. This not-subtle nod to an anti-colonial critique is in sync with the nihilistic storyline.

By removing the potential fealty both player-characters and players may have to any specific nation or faction, the conflict being presented winds up shallow by design. These battles are not going to decide the fate of the free world or alter the course of history. This is just a fight for survival for all those involved. Few military shooters set in the modern era have been able to thread that needle.

So What?

What, ultimately, is the utility of this analysis? Although I remain convinced that Escape from Tarkvo is lamenting war in which it is set, it hardly represents an act of protest. I’ve arrived at my conclusion of the game’s stance on violence by finding patterns in its mechanics and undertones in its storytelling, not by reading overt signposts. If the thesis takes this much effort to unearth, what purpose could it serve?

In an era that has us rightfully examine our media consumption for biases, I find this observation meaningful. Far more than desensitization to violence, we should remain wary of glorification of war in terms of the real world consequences of poorly thought out stories or lazy narratives in games. A player coming away from Modern Warfare or Battlefield may find themselves excusing, minimizing, or even idolizing, war. A player spending a significant amount of time in Escape from Tarkov will come to think of war as a brutal, hopeless waste of time, resources, and lives. Given the two options, I hope we see more games communicating the latter set of values, even if you have to dig below the surface to find it.